Introduction

It’s only fair to begin with a “before” photo. I’d been on this Collette tour for eight days before all hell broke loose. Confident, enjoying the adventure, I’d followed the tour guide through the sights in Malaga, Cordoba, and Seville, enjoying the camaraderie with the group of 16, the food, and of course, the wine. I had no idea what was about to transpire or to what extent and for how long it was going to change my life.

Day One, April 23, Sunday

We’re leaving Seville after two nights. I’m exhausted from the pace, as I always am at the end of a tour. It will be a long drive today to Portugal with stops along the way. I’ve decided to give Fernando, the tour guide, my book about the humor in aging, so he can peruse it during the drive. Fernando is 62, average height, with thinning hair, a bit of a beard and an inviting smile. He’s full of energy and jokes about his country. He’s a boomer, laughs at my jokes, and is intrigued that I write books. I’m all ego. I want him to like my book. Maybe start a flurry of sales in Spain.

The bus rolls down the main city boulevard, stopping for lights. I get up out of my office, as Fernando has dubbed my seat behind the exit door on the right side. Most of the others are changing seats every day, but not me. My seat has a nice little table to put the camera on and a good window for taking pictures. I scoot down the aisle, toss the book onto Fernando’s bags and go back towards my seat. I’m almost there, grasping a seat handle, when the bus lurches and I lose my balance. I go down on my right side, no biggie: my head ends up resting under a seat. I would probably be just a bit bruised, by my left leg has caught on a chair leg or the exit steps and it doesn’t come with me when I go down. Body vs. leg. I don’t have a chance. I lie in agony. The bus pulls over, Fernando comes. I feel like an idiot, an idiot in excruciating pain.

Fernando says, “You’ll be OK. We’ll get you up in a minute.”

“I don’t think so,” I answer. I don’t know if something is broken but my inner thigh feels like it’s been ripped apart. At the least, I need an x-ray. This is the end of the tour for me.

Several from the group get off the bus to look for ice, but come back empty-handed. Paramedics arrive promptly and the tour group is forced to listen to my screams while the pros struggle to get me on their board and off the bus. They put me and my luggage into the ambulance. Fernando accompanies me for the short ride, wishes me well, and leaves me at the ER at Virgen del Rocio University Hospital. It’s the public hospital, which doesn’t mean much yet.

It‘s 9:30 a.m. when I first look at my watch. I remain all day in the enormous space that is the ER. There are no privacy bays. Every time they move me, I scream, but I don’t seem to be in shock. I repeat to myself over and over how stupid I am to have left my nice, safe seat on the bus. How I’ve screwed up everything. But I’m sober and in control of my emotions, if not my body. I have no choice but to deal with what has happened.

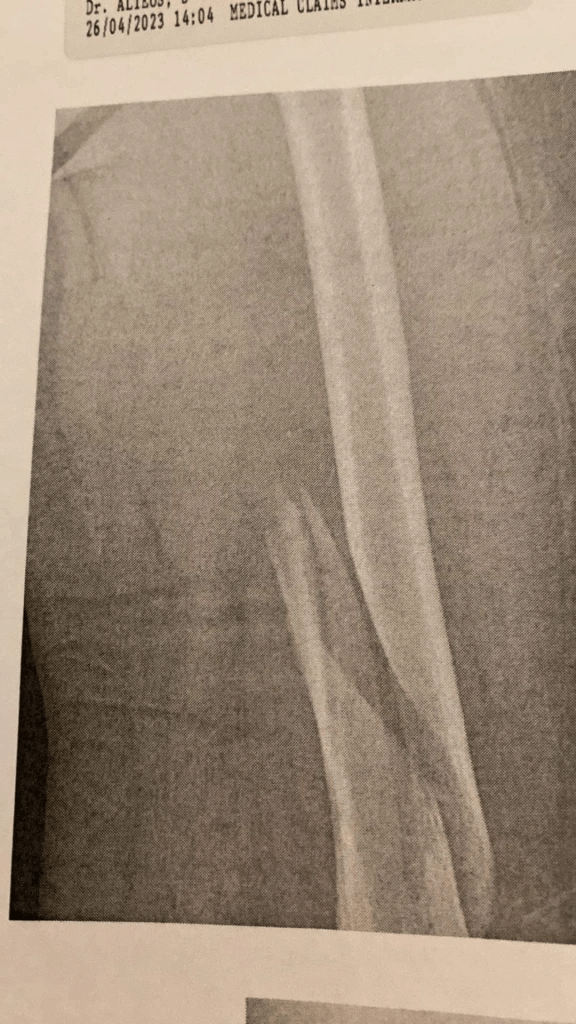

They take me for X-rays and return me to the big room. I meet the trauma doctor in charge, Dr. Moreno. He’s in his late 30s, with dark hair and eyes, a kind manner, and he speaks English, unlike everyone else I’ve encountered in the ER. He tells me my femur is badly fractured and I need surgery. But not in his hospital. They wouldn’t be able to do it for a week or more. And it’s too serious for me to fly back to the US.

A brusque woman comes by and asks if I have insurance. I have someone get my tour documents out of my bag and I begin making phone calls to Collette Tours and their insurance provider, Zurich, in Canada. I’m lucky I bought that insurance.

I text my brother, my niece (who is coming with her husband to visit me in California in three days), my dog sitter, my special neighbor and friend Bill, and Susan, who has my power of attorney for medical decisions. Not that anyone in Spain will ever ask me for it or if I have a DNR.

After three hours, I tell an aide I need to use the bathroom. They give me a bedpan and cover me with a blanket. Lifting myself onto the pan is painful and it’s gross to relieve myself in this way in an open space. But what choice do I have? My new theme song. Several hours later, when I ask again, they take me to a private room, pull off my clothes and put me in a hospital gown and a diaper.

By evening, mid-day in Toronto where the insurance company is, I have a case number, but Zurich needs a report from a doctor before they can approve a claim for services. The young, jabbering aides move me to another staging area. Mostly female, all twenty-somethings, they flit around like birds in a tree, constantly talking to each other. They ignore my pain. One brings me a bracelet with my name misspelled as Lendre and the month and day of my birthdate reversed. I tell her the corrections and watch her walk away without changing anything.

I’m lying there and a crew of girls standing at the foot of the bed tell me in Spanish they’re going to move me down the bed. They have my feet in their hands. I tell them in English I can use my good leg to push myself down and bend my leg to show them. Would they pull on a broken leg? Apparently so. I demand, “Don’t do it. Let me do it. You’re going to kill me,” but they go ahead and pull on both feet. I scream, “Tortura!”

Much of my limited Spanish I know from volunteering with an organization that helps legal immigrants fill out the paperwork to apply for US citizenship. I have to ask every applicant if they’ve ever tortured anyone. Of all the Spanish I might expect to use, this would be at the bottom of my list.

Now they think I’m a nut case. They explain they are going to put my foot in traction. Several times in between sobs, I say, “Quiero hablar con el doctor.” I want to talk to a doctor before they do anything else. They argue and go right ahead. The traction is not that bad; it may keep my leg from moving, but I trust nobody. By this time I have an IV. Gimme some drugs, please. Perhaps I’m being admitted.

A nice doc comes over who speaks a little English. I tell him I need a report for the insurance company in order for them to approve the claim. He says he’ll go write one. But in the next few minutes, they move me to a room and I never see that doctor again.

A young man pushes my bed to the elevator, up a few floors, and down a long quiet hall. Despite my pain and disorientation, I feel like I’m finally getting to a place where I can settle and rest. We’re greeted by a nurse who questions the fellow pushing me. She seems to think this is a bad idea. But she and her compañera slide me from the ER bed to the hospital bed by the open window. I scream some more, as every slight movement of my leg is excruciating. The room has no AC and no screens on the windows.

The nurse makes a big fuss, seeming to ask in Spanish if I have money. I get out my purse. No, she just wants a Euro coin, which I don’t have. She says it’s important to lock up my luggage and my purse in a locker and the locker requires a Euro to open. She goes off and comes back with a coin, loads up my stuff and makes a little wrist bracelet out of some string so I can wear the key. She makes it clear things disappear in the night.

Before long there are two men on the other side of the room. “Hola?” I say. Could they be the thieves? They tell me their wife/mother will be joining me. As I try to settle into my new reality and let the drugs do their work, there is much talking coming from the other side of the screen. The wife is brought in and the husband ends up spending the night. I can’t understand anything they say. He moves the furniture around noisily and someone on the other side of the screen snores all night long.

Day Two, April 24, Monday

I finally get to sleep after midnight. I know this from my Fitbit, which I check every couple of hours during the night. It also tells me my resting heart rate is quite elevated, a sign of my body’s stress.

In the morning, I want to check my email, but the hospital requires payment for WiFi, and the system is wonky. A monitor on a mechanical arm sits by the window beyond my reach. The nurse moves it closer and gets my purse out of the cupboard so I can retrieve a credit card. The WiFi requires me to enter a long access code every time I login. I pay for a day but still need to reenter the code every time I log on. This mental pain may not be as bad as the physical, but it too makes me want to scream.

I feel less alone after emailing people back home, posting on Facebook, and making calls once it’s late enough in the day to do so. Two of my loved ones offer to fly over and assist me. I tell them they’d only be watching me wait for something to happen. When I end the calls, however, the loneliness and fear settle back in. It would be so much better to have someone holding my hand.

I continue my conversations with the insurance company, Zurich, in Toronto. Yesterday they told me their phone number works 24/7, but today the recording says their office hours are 7 to 7. At first my addled brain thinks that’s 4 p.m. to 4 a.m. Spanish time. I wait all day to talk to them. They have offices all over and I try three or four other numbers, but all go to the same recorded message in English and French. In time I learn it’s only a six-hour time difference, but I still can’t accomplish anything until mid-afternoon.

Learning to pee in a diaper is humiliating but necessary. I tell myself, “You’ve got to do it, girl, push.” Diaper changes are painful, as every time the nurses roll me over, the two pieces of my femur want to move. The first time I don’t know you’re supposed to call for a change immediately. With the next pee, there’s a flood onto the bedding and they have to change the sheets. More rolling me over. They’re big on cleanliness, so I get a bath in the bed too. I’m quickly past any modesty and appreciate being cleaned up, but these nurses are all business. There’s not much gentleness or concern for how I’m feeling. They use a wet cloth to dab at my face. Don’t they realize if they handed it to me, I could wash own face? I guess they’re focused on speed. They have other stuff to do.

They bring me food, which I pick at. Food and drink means more pee and eventually poop, in their lingo, officially “caca.” All I need do is ring the call button and say “pee pee” or “caca” and they get to me—eventually. I clock one yucky change at a two hour wait. It makes me think about the fate of all those oldsters in nursing homes, unable to receive the attention they need.

I also spend time thinking about people caught for days in the rubble of collapsed buildings. I share their fear, the anguish of hunger, peeing on yourself, not knowing if you’re going to make it and having no control over the situation. At least those folks can yell and hope for rescue, but that won’t do me much good.

Meals happen four times a day. Breakfast, around 8:30, is the same every day: a plain roll accompanied by olive oil and a tomato spread, and a cup of warm milk with a packet of instant coffee. Not quite a Starbucks latte, but not bad. The Spanish are very big on their olive oil, as the entire country is covered by olive trees (Fernando said 6 trees for every person–it amounts to 300 million trunks of grey-green leaves shimmering in the breeze.)

Lunch is not served until 1:30. There’s soup or a bowl of cooked vegetables, chicken or fish or beef with a spicy sauce, which I scrape off. Yogurt or pudding for dessert. And a small bottle of water. I keep every one of the precious water bottles. There is no nice sippy cup with ice water that we have in American hospitals and one taste of the tap water tells me to avoid it. Not to mention I’d have no way to get it!

You’re supposed to take a siesta after lunch, and then at 4:30, they bring La Merienda—like tea time, but with coffee. Some cookies, a muffin or crackers and another cup of warm milk with a packet of decaf instant. I rather enjoy this snack every time. That would be enough food for me, but somewhere around 8:30 in the evening they bring dinner, a full meal just like the lunch. Pain and exhaustion keep me from sitting all the way up. I pick at the dinner, hoping to avoid reflux and get to sleep.

I still need a report from the doctor. Doctor #3 comes by on rounds. I get no smile, no bedside manner. He says something to me in Spanish, which I don’t understand.

I give it my best shot. “Senor, necesito a report por el seguro.” Or something like that. I’m trying to tell him nothing is going to happen until the insurance company gets a report. He must understand me because he talks into his phone at bullet speed in Spanish and then hands it to me to read three paragraphs translated into English. It says the hospital will release none of my records to anyone but me, they will not talk to anyone on my behalf, and there’s not much they can do for me. I need to move to a private hospital.

I think I hear “Voy a escribir el reportaje” before he leaves.

It’s Monday and I hope he provides the report in time for me to have surgery by Wednesday and fly home by the weekend. Silly me.

Late in the day, I finally reach Zurich. They ask if there is an accident report from the tour guide. It seems to me they could ask Collette Tours that question, since only Collette would have requested an accident report. But I obediently text Fernando, who may regret giving me his number, and give it to Zurich. Now they want a picture of my booked plane reservations. God, why can’t they get that from Collette? I take pictures of what’s in my tour booklet and email them. It hurts too much to sit up, so I’m holding papers on my good bent leg with one hand and taking pictures with the other.

My smart phone is my only connection to those who can help me, and to home. Keeping it charged is the most important task of my day. I entertain myself with games on the iPad, balanced precariously on my tray table, and keep one of my devices charging at all times. I’m already starting to get ads in Spanish. At night, rather than having my electronics locked up in the closet, I bravely slip both into the drawer in my table, hoping a thief won’t try to get past me to steal them.

It occurs to me that even if I’m home by the weekend, I won’t be able to do what’s on my calendar, so I send emails to let the writers’ club and church know I won’t be attending. I message back and forth with my niece so she and her husband can get into my house and find the things they need for their weekend stay. I hope they enjoy their visit without me!

In the afternoon, my roommate is again visited by her family—3 sons and a daughter, lots of laughing and talking. The upside is they help me take things in and out of my locked up bags, adjust the windows, and pick up my glasses or my phone when I drop them on the floor. Nightfall comes again and I wonder when I’ll be moved to a private hospital. When I’ll have surgery. I’m sweating profusely during the night and it’s not because the room is hot. What can that mean?

Day Three, April 25, Tuesday

A friend emails to ask how I’m feeling. My answer: like I’m in purgatory, after three days in a hospital bed on my back, unable to move. My damp backside is stuck to paper products. I’m worried about getting bedsores on my back and/or an infection in my injured leg, but there’s nothing I can do.

The bath crew comes in and I’m suddenly aware that someone has body odor. A quick sniff under my gown reveals it’s me! Nobody has offered me deodorant or toothpaste. I make a face and point and they get the message to give my pits a good scrub. I pantomime brushing my teeth, but they tell me they have no toothpaste. I say, “Yo lo tengo.” At my direction, one aide retrieves my toiletry bag from my luggage and brings me a basin to spit in. Small pleasures are such a treat!

The gruff doctor comes through with a report (hallelujah) and I take pictures of it with my phone and email it to Zurich. They also need me to docu-sign an online form with details of the current hospital. They also want a list of all my doctors at home, including their addresses and phone numbers. I have to google these superfluous details. Dare I refuse? I can’t do anything that might delay surgery. The docu-sign doesn’t work on my phone, so I send them a screenshot of what I have entered.

Now that Zurich has the report, how will they select a private hospital? I ask Google what’s available in Seville. There are many hospitals here; none have high ratings, but I find two that look like comprehensive modern hospitals. Do I have to choose one?

Dr. Moreno from my first day in the ER comes by on rounds. Knowing he understands English and remembering the pain of being moved from one bed to another, I ask, “Doctor, before they take me to the other hospital, can you increase the pain medicine?”

He nods, but I’m not sure that means he agrees or just that he understands the request.

If you’ve ever slept with your head higher than your feet, you know the inevitability of slowly sliding down, until your feet dangle off the end. I have a weight hanging from my foot. I swear it’s an ordinary brick. I guess the purpose is to stabilize the femur, but it only encourages my downward slide. When I use my good leg to scoot back up, despite the morphine in my IV, pain sometimes shoots through me. When two nurses are present, they lift the brick off the floor, grab my shoulders and pull me up. When I’m alone, I reach above me, trying to grab the bar at the top of the bed. If I can, I grip it and pull myself up, convinced I’m working on arm strength, which I’m going to need if I ever get to a wheelchair.

It’s hard to explain the raging discomfort that comes from being flat on my back for so many days, unable to turn over, sit all the way up, or stand up. Screams swell inside me, but only emerge when my physical pain is extreme. I have no choice but to accept things as they are and deal with it.

Zurich emails me that my claim is approved. Yay! I will be moved to a private hospital, Quiron Salud Sagrado Corazon (Sacred Heart). It’s one of the two hospitals I identified as looking good. They are waiting for their “local correspondent” to make the arrangements. How long will that take in Spanish time?

My dear friend Susan, in Washington, D.C., whose partner works for the state department, texts me that I should contact the US embassy in Madrid or the consulate in Seville. She provides me with their phone numbers and websites. I look at the embassy’s site, but can’t figure out how to send them a message. I try the phone of the local consulate but the call goes nowhere—no ring, no machine. Perhaps I haven’t entered the country code correctly. I give up. What can they do anyway?

Once again, my roommate has visitors late into the evening. Her English-speaking son tells me she broke her femur in a car accident on Sunday. She had surgery the same day and two days later is still in bed all the time. I thought after surgery I’d be able to get out of bed. After knee replacement, I was up the same day and had an occupational therapist help me to take a shower. Where’s the therapist to help her with a walker or a wheelchair?

When the roommate’s family leaves, she babbles at me in Spanish, but all I understand is that her name is Dolores. I keep repeating, “No comprendo,” but also tell her I am from California, a tourist, and alone.

Day Four, April 26, Wednesday

I am usually obsessively organized, but here I don’t have easy access to my belongings; my bags are locked in the closet. I saw someone roll up the clothes I wore on Sunday and shove them into a dark plastic bag. When the roommate’s son opened my carry-on to get my charging cords for me, I saw my shoes stuffed into a shower cap! Somewhere in the mess of luggage is my jewelry. No diamonds, but it’s still precious to me. I figure when they give me information about my transfer, I’ll ask a nurse or visitor to open all my bags and rearrange things. But mid-morning, with no warning, three paramedics show up to move me to the new hospital. I’m feeling woozy, so perhaps Dr. Moreno did give me stronger drugs.

They transfer me from my bed to a gurney with no difficulty, although I keep wondering if I’m going to throw up. These medics are much more professional than the hospital staff. In no time I’m in the ambulance and soon arrive at Quiron Salud. The hospitals are practically next to each other. I’m not in pain, but nervous as I anticipate what will happen next. When they wheel me in, I am struck by cool air and stare up and around at the clean, bright spaces of the modern facility. They park me in an admissions area where I wait with other sick and broken folks for paperwork to be completed; I listen with concern to one young woman who looks miserable and coughs constantly. I hope it’s not Covid. That’s the last thing I need!

Finally, it’s my turn. The young female admissions person is congenial. She asks, “Where are you from?” and my answer elicits the usual oohs and aahs about how wondrous California must be. She begins inserting an IV in my arm, while carrying on a flirtatious conversation with two young men who work there. She smiles at them, they tease her—I have no idea about what. She pauses while holding the needle to my arm to give her undivided attention to them. Unbelievable! I get a new wristband. Now I am Leonore. It’s an improvement over Lendre and I take no offense, as some version of this name is the Spanish equivalent of my own.

My new room is like a hotel compared to the last hospital. It’s a corner room, private, with just one bed, an armchair, and a sofa someone could sleep on. Two walls have windows with outside louvers that go up and down by a switch on the wall. There’s a bathroom, which I don’t get to see much. WiFi is available and free. I have a wide screen TV, but everything on it is in Spanish and sometimes all I get is repeated instructions for how to buy access through a machine in the lobby. I eventually find music channels I can play for free and cheer up listening to American oldies. “I think we’re going to make it.” I can get on board that train.

The constant translating is wearing on me. Every day someone is in my room asking questions and I don’t know what they’re saying. Or I need something and have to look up how to say it in Spanish. I’ve downloaded an app for translation, but it’s not consistently good. Or I use my bad Spanish to no avail. I try to tell a nurse I have a sore on my back. “Tengo un dolor en mi dos.” Unfortunately, dos is the French word for back, but in Spanish it means two. Or trying to tell a nurse I have dropped my glasses on the floor, I say, “Por favor mis lenses estan sur la plancha.” But plancha means plate and all I get from her is a blank look until I point and she sees my lost readers.

I foolishly hope my surgery will be tomorrow morning, but no doctor makes it in today, so I’ll have to wait and see. In one of my conversations with Zurich, I share my anxiety about the delay of treatment. “Look, it’s been four days and I’m afraid I’ll get an infection if they don’t do surgery soon.”

The agent listens patiently. My throat seizes and the tears come when I tell her, “I don’t want to die in Spain.” I talk about my frustration trying to communicate my questions and needs to staff who speak only Spanish. She responds that in some cases, the insurance will provide travel for a companion to provide “comfort.”

Which of my friends speak Spanish and might be willing to fly here? They could sleep in my room! Who would be a help, not a hindrance? I develop a short list of possibilities. I write to my top choice, who is also a psychologist. She helped me out long ago when I had a traumatic occurrence at school. But she is unfortunately ill and it turns out to be pneumonia.

Today is the day I was to fly home. The tour is now over for everyone. It’s sinking in I’m going to miss more than the weekend. I ask my dear friend and neighbor Bill to get my calendar from my desk at home, scan the May pages and send them to me, so I can start canceling more of my life. I’m so glad I bought the $10 a day plan for unlimited phone use. I’m getting my money’s worth.

I have two sore spots, one on the back of the injured thigh, where the skin is peeling off, another on my right buttock. Bedsores, I presume. I show the nurse and she applies a bandage. It’s no surprise when the IV so carelessly installed by the young admissions gal falls out. I ring the call button and get a new one.

Late in the day I receive a text from the driver who’s at SFO to pick me up. Collette didn’t cancel the booking. What a waste. And how I wish I were there, not here in a hospital bed, thousands of miles away.

I send an email to my brother: If I don’t make it home, please use my money to do something to help people in need. I shudder to think of him buying a fast car or a boat, or a famous singer’s guitar. Yeah, he just might do that.

Day Five, April 27, Thursday

My hospital room may have AC, but my room is hot and stuffy. The windows were open all night and the morning air flows in warm and moist. The sun streams into this space several floors above the street. I ask the first person who enters my room to close the windows and the louvers, to keep the heat out. Two nurses come in to bathe me and I ask, “Es posible lavar mi pello?” I’m not sure those are the right words, but I point at my greasy head of hair. It’s been 5 days! They tell me something about a beauty salon in the hospital, but then ask, “Ahora?” Now? Yes, please!

Bless their hearts, I am going to forever remember these two lovely women. The more experienced one is named Pepa. They get a plastic bag to hold the water and help me scoot up the bed so my head is over the edge. They give me a shampoo right there, managing to keep the rest of me dry. I haven’t been this happy since the accident. I start calling Pepa and her compañera my Angeles de Pee Pee. They laugh.

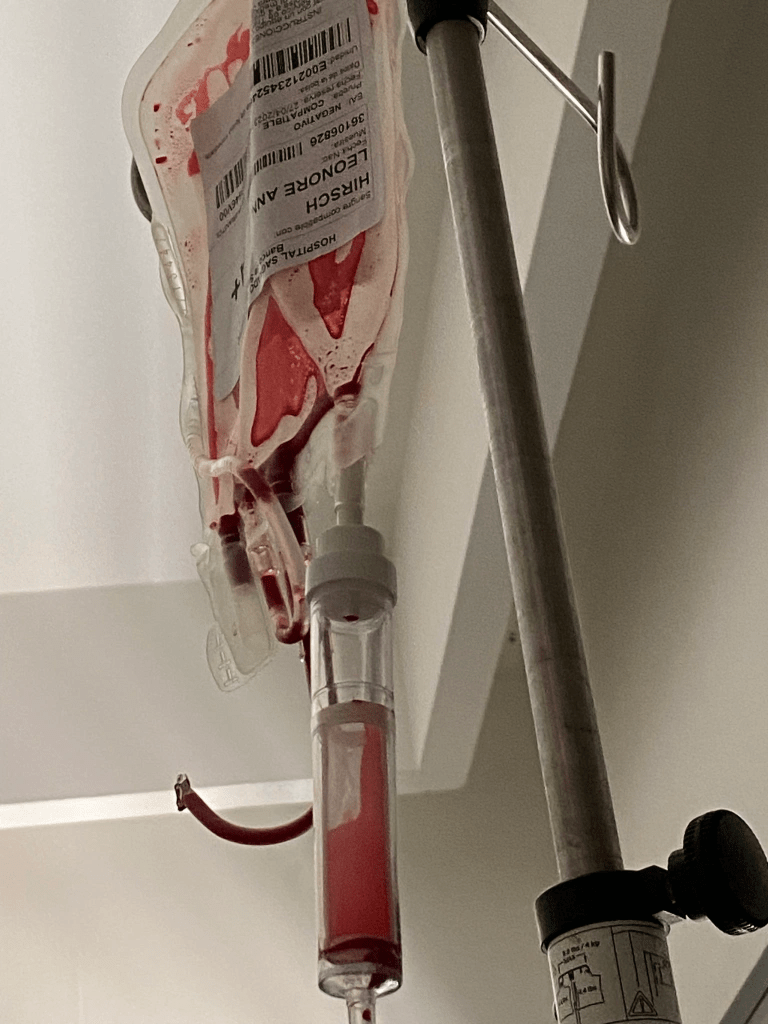

The doctor arrives! Dr. Gonzalo de la Cuesta. He’s a kindly old guy, which puts me at ease. His English is halted, but if I speak slowly he understands me. They’ve done some testing and he tells me I have lost too much blood to have surgery. He says, “Normal hematocrit is 14 and yours is 7.”

“Doctor, I’m afraid I’m going to die.”

He shines a warm smile on me. “You’re not going to die.”

“I am sweating mucho at night. Don’t I need antibiotics to keep from getting an infection?”

He shakes his head. “We only give the antibióticos during and after the surgery.”

The end result: more waiting. I hope for surgery tomorrow, Friday. If not then, will I have to wait until Monday?

A maintenance man comes into my room for some reason and I point to the AC control on the wall and say, “No trabaja.” I don’t expect any results from this, but a bit later, he returns with another worker and a ladder. He climbs the ladder, removes the vent from the ceiling and cleans it. Suddenly I’m getting cool air. I have them set it as cold as it goes. Now everyone who comes into the room wants to adjust it, but I say, “No, por favor, me gusta.” They all think I’m nuts.

A nurse comes in with a pint of blood and hooks it to the IV pole. I’ve seen many bags of blood, but only when I’ve been at a center to give blood, which I’ve done my whole life. I’ve never thought about who receives my blood. This is a new experience. Now the bag hangs from the IV pole and the blood is going into my arm. The nurse says to ring the call button if I begin to feel weird. What’s that about? Is there a possibility of a bad reaction? I feel fine. Grateful tears flood my eyes. When the bag is empty, a second one takes its place. I wonder long and hard about where the blood came from. I get out my iPad and write a poem.

My Facebook posts have brought offers of help. I get a message from a woman I don’t know well, but who is a Facebook friend. Her dad is a retired orthopedist. Would I like to get a second opinion from him about my injury? Sure! I send her my x-ray. She also worked as a hospital social worker, and gives me advice about traveling home with medications. I ask her what she or her dad knows about the use of antibiotics before surgery and wait for her to respond.

I’ve had two pints of blood. Perhaps my surgery will be tomorrow.

Day Six, April 28, Friday

I eat the breakfast they bring, hoping the surgery will be late in the day. Dr. de La Cuesta comes by before noon. He says my blood level is better, but it’s still not good enough for surgery. They’ll give me one more pint of blood. The operation will happen on Saturday or Sunday.

I swallow my disappointment, laugh and ask, “Do you work seven days a week?

“No,” he answers, smiling. His colleague will do the surgery. “He is younger and more skilled,” he says.

I guess that’s a good thing, but I haven’t met this colleague.

Then he asks, “Your prosthetic knee, what kind is it?”

Perplexed, I answer, “Titanium?”

The break in my femur is periprosthetic, close to the artificial knee, so he needs to know more about my prosthesis. Like who manufactured it. Something about whether it is a “rear motion” device. This means nothing to me. He gives me his email address and leaves me to ponder how I’m going to get this information. Does this mean I can’t have surgery until I find out who made my knee? OMG!

I am at the end of my rope. I text dear Bill, who has been clamoring to help me: “Go to the airport.” I just can’t handle any more. In no time, he gets back to me. He’ll leave Saturday and arrive in Seville on Sunday early in the evening. I send him information about hotels near the hospital. He makes a reservation. I begin to relax.

How can I find out more about the prosthesis? Do I need to wait until my Napa orthopedist’s office is open and call them? Will they be able to find the information from five years ago? Then I recall I’ve got info from my knee replacements in a file at home and my niece and her husband have been in my house since yesterday. Their long weekend to visit me hasn’t exactly turned out as planned, but they’ll be there until Monday. I wait until mid-afternoon when it’s 6:00 a.m. in Napa and call her. She uses her cell phone to navigate in the dark.

My obsessive organization comes in handy sometimes! I talk her through opening the right file drawer, locating all the medical files and finding alphabetically the one labelled “Ortho.” A scientist by training, she has no trouble reading through the medical language to find the operational report. She takes a picture and sends it to me. I forward it to Dr. de la Cuesta.

My dear Susan is still pursuing the embassy. She copies me on an email she has sent to Madrid, referring to me as her step-mother, a slight exaggeration. She has also somewhat exaggerated my situation, saying I am desperate for help. The embassy probably won’t see her email until Monday.

I hear back from the friend with the ortho dad. He says my need for surgery is indeed critical. Because the break is close to the prosthesis, it limits the surgeon’s working space. He agrees with de la Cuesta that there is no need for antibiotics before surgery. This reassurance should give me confidence, but now that the surgery is about to happen, I can worry about all the things that could go wrong. I’ve told the doctors that opiods make me sick to my stomach and that the drug usually given for nausea doesn’t work on me. Will the surgeon have the skills of my doctors at home? Does their operating theater have all the bells and whistles I’m accustomed to? Computer guided surgery? After a week on my back, am I in good enough health for surgery? There is no end to my questions, but there are no answers. Once again, my only choice is to accept the circumstances I am in and hope for the best.

Day Seven, April 29, Saturday

Yesterday the doctor told me to have no food or water in the a.m. That means surgery. But the nurse comes by with breakfast.

I object, “Pero el doctor dice …”

“No,” she says, “cirugía mañana.”

Another disappointment, but at least I have been finally given a definite date for surgery! And I’m hungry. The surgeon, Dr. de la Cuesta’s younger and more skilled associate, comes by to introduce himself. Dr. Roman doesn’t speak English, and is very brief. At least I’ve had a look at him. Medium height, dark hair and eyes, in his forties. Then the anesthesiologist arrives. This is the guy I need to talk to about my past surgery issues. He explains I’ll have a spinal. That doesn’t mean much to me. He doesn’t mention Fentanyl or other calming drugs routinely used in the US to give the patient no memory of what happened. Fortunately, he knows English, so I tell him about the antihistamine I’ve learned keeps me from vomiting after surgery—Promethazine. He takes the time to look it up on his phone and after several minutes of searching and reading, tells me it doesn’t exist in Spain. Well, I tried. They bring in a machine and do an EKG. Looks like it’s really going to happen.

Bill’s flight has left San Francisco. I text him my room number, promise to brush my teeth for the kiss he is anticipating. Only in a Spanish hospital would I need to make special plans for that! I text the insurance company with the surgery schedule. Now they can start worrying about getting me home. I’m already into it. When will I be able to fly? And how can they book flights without knowing?

The tour guide, Fernando, has been in touch almost daily, concerned about me.

He texts me: I am jealous that you have a boyfriend who is not me.

Very cute. I text back: I feel bad that you didn’t get your tip.

He responds: No worries.

I ask: Do you use Amazon.es?

Yes.

I send him an electronic gift card. So easy.

Day Eight, April 30, Sunday

I can’t believe it’s been a week since the accident. I’m nervous about the surgery, but long to be on the other side of it. Mid-morning, they wheel me to the operating room. Someone inserts a needle in my back.

To my surprise, I’m awake during the whole procedure. I feel little until near the end. I hear the docs talking to each other, hear them drilling away from me, hear them drilling in my leg. They’re putting in a plate and screws. Suddenly the doctors are yelling at each other, “Plaque, plaque!” Do I have a blood clot? What could it be? Maybe they’re just talking futbol.

Near the end I feel the doc squeezing my leg, as if to close the incision. My voice seems to be anesthetized, but I muster some strength and say softly “Should I be able to feel that?” I get no response. Perhaps they didn’t hear me. A few minutes later, I feel the staple gun at the north end of the incision. It hurts, just a little. I say, louder, “That hurts.” No response. I feel what I think is stitching going up the lower end of the incision. These docs don’t acknowledge my input, but it’s finally over.

Soon I’m back in my room. I’m thrilled I’m not nauseous, my usual response to anesthesia. After a while a young man comes in to take me for x-rays, but it turns out to be comic relief. He wheels me into an elevator and to the radiology room on another floor. The first time I was here, they moved me from the hospital bed to the fixed platform in the middle of the room while I yelled that it hurt. This time it seems they don’t want to move my body. A young woman comes out of an inner office and the two of them manoeuver my bed around the room. They adjust and readjust the x-ray machine on its arm attached to the ceiling, trying to figure out how to get the pictures they want. They bump the bed up against a wall, turn it around part way, try to reposition it, bump up against another wall. It’s hilarious, but I’m not laughing. This is a modern radiology department? They finally take some pictures and return me to my room.

It’s evening and Bill walks through the door, all masked up. He gives me a hug and I cry. I knew I would. He’s upbeat, happy with his hotel, where he just checked in, dropped his bags and came straight to me. Perhaps the nightmare is over. I’ll have someone by my side to get through the rest. He doesn’t speak Spanish, but being able to converse in English is an absolute delight.

Around nine p.m., a nurse comes in to give me an injection of Heparin in my stomach, to discourage blood clots. She also gives me a cup with two big pills in it. This is Paracetamol. I look it up on my phone. It’s the same as Tylenol. I take them and then read the recommended maximum dose is 1 gram and they have given me 2. Somebody made a mistake; I hope my liver survives. She also gives me another drug, Enantyum, an NSAID, compared online to ibuprofen but a lot stronger, only 25 mg each pill. It makes me sleepy, which is fine with me.

Dr. de la Cuesta has said I won’t be able to try sitting up or getting out of bed for two days after surgery. At least I won’t be bothered by wet diapers until the catheter comes out on Wednesday. They have left a needle in my back to deliver pain medication. Sleeping on my back all these nights is making me crazy. I sometimes snore through my nose and never stay asleep longer than a couple of hours. I long to turn on my side. Two more days to endure being flat on my back. That will make a total of eleven days immobilized. For now, I’m just glad I survived the surgery. There will be an end to this story, perhaps a happy one.

Day Nine, May 1, Monday

Bill texts he’ll be by to visit after breakfast. That could take a while, as the hotel breakfasts here include everything one could possibly want. Besides the usual assortment of meat, cheese, eggs, fruit, cereal and bread, I have been to breakfast buffets that included cheesecake and sparkling wine.

Now that my gentleman friend is here, I’m aware I must look like hell, but the only way I can check is to use my phone in selfie mode. That’s never a good look, but I see dark circles under my eyes. No hair dryer, no make up for all these days. Tooth brushing maybe once a day. I’ve squirreled my toothbrush and paste into a bedside drawer, and I always have water, but have to wait for someone to bring me a basin to spit in.

Dr. de la Cuesta comes to see me early. The doctor explains they don’t use oral opioids after surgery, which is fine with me. Thus, the first two drugs last night. The third drug they give me is Nolotil. I find several recent articles about how it is the most often prescribed NSAID in Spain and Portugal, but nearly twenty visitors from the UK have DIED after taking it. I tell the nurse and later the doc, I’m not going to take it. Dr. de la Cuesta nods his understanding.

I ask, “When will I be able to fly home? By Saturday or Sunday?”

He answers, “Probably. We’ll see.”

How will the insurance company arrange for flights when we don’t know when I’ll be released? There always seems to be something new to worry about.

I’m now on IV antibiotics and there is a drip still attached to my spine. I have no idea what drugs I’m getting, but I’m thrilled to not be nauseous. The nurse says the catheter will be removed on Wednesday and I’ll be able to sit in a chair. My goal in life: to sit in a chair!

Tour director Fernando has received my Amazon gift card. He writes: I’ll use it to buy your books! Funny guy! I send texts to all my friends and post on Facebook that I survived and hope to be home soon.

Susan’s message to the Madrid embassy has clearly been received. Late in the morning, when Bill is with me, a woman appears who is the hospital’s Director of Patient Relations. Maria is fluent in English, very friendly and personable. We learn all about her visit to Mexico, where her husband, doing bullfighting, fell and broke his shoulder. Their misery was compounded by the fact that they hadn’t bought travel insurance. She answers all my questions and asks permission to give my phone number to the Seville consulate. A representative there calls me later in the day and expresses concern. I assure him I am being well cared for. I’m thrilled to now have a direct line to a hospital employee who can help me.

Day Ten, May 2, Tuesday

Bill has booked a tour of the cathedral for today. I’m happy for him to get some time to see the city. He doesn’t need to be with me all day. But it’s great when he comes by in the afternoon, bringing me a Diet Coke and ice and a cookbook for tapas. For a man not committed to an exercise program, he is doing a lot of walking in the heat. Several trips a day back and forth between the hotel and the hospital, plus around town. He is having most of his meals at the hotel. He has an adventurous spirit, although not knowing Spanish is a challenge for him.

Today, a third doctor comes to visit and I love his name: Fernando Avila España. He’s a big guy who speaks English beautifully and has been to the US. When he hears I’m from Napa, he goes on and on with a broad smile about his daughter going to Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles and the wonderful time he had when he visited San Francisco and Napa Valley.

Dr.España has brought me a brace for my leg and recommends I put it on whenever I am out of the bed. It will hold my leg straight for the trip home. He is very proud of the design. Created by a Spanish company, but sounding like a copy of a German product, it has a switch that will enable me to bend my knee when needed, while still protecting the repaired bone. The cost to me, 200 euros. I invite him to visit Napa the next time he’s in the US.

Now I’m working with Zurich about the transportation home. So soon after surgery, unable to walk, with my leg needing to be kept straight, how am I going to handle a trans-Atlantic flight? I don’t want to fly in a diaper or with a catheter. Google tells me that many airliners have handicapped restrooms and little wheelchairs to get you there. That’s a relief. Zurich wants to know what day I’ll be able to fly. It’s hard to know, as I still haven’t been out of the bed, but I say Saturday or Sunday. Bill wants it to be Saturday, as he has his own plans for dental surgery on Tuesday.

Day Eleven, May 3, Wednesday

Every day I am giving more thought to what it’s going to be like when I get home. I’ll need to see a local orthopedist for follow up. I’ll need medications. And I’ll need a wheelchair from the moment I arrive. How am I going to manage that? On Facebook I see that my acquaintance Betty has mentioned she volunteers on Wednesdays at Share the Care, a local place that lends out medical equipment. Hey, it’s Wednesday. I send Betty a message: Any chance you can deliver a wheelchair to my doorstep for my arrival on Saturday? My wonderful cousin Lyn, who lives nearby, offers to stay with me for the first week or so. I tell her how to find a key to my house and she promises to be there when Bill and I arrive.

A nurse removes the catheter. Another milestone reached. Two male attendants sweep into the room, grab the corners of the sheet I am lying on, like it’s a sling, and place me in a chair. It happens so fast, I don’t have time to fear I’ll fall out of the sheet. I imagined this big step forward would be overseen by an occupational therapist, but the two fellows are out the door as quickly as they arrived. My leg hurts; hanging bent it doesn’t reach the floor. A nurse shows us how to use a pillow from the sofa as a footrest. Bill and I experiment with different combinations of pillows to provide the most comfort. It’s wonderful to be truly upright for the first time, but after about an hour, I’m exhausted. We call for the two muscly guys to use my sheet sling to move me back to the bed. How am I going to fly home in two days? There is no way I could do this on my own. I’m so grateful for Bill.

Day Twelve, May 4, Thursday

Bill has noticed a walker outside my room. Dr. de la Cuesta comes in and we talk about how I am going to handle the airplane ride. He tells me I must put no weight on my leg for four to six weeks, but I can use the walker to hop to the bathroom. He guides me the first time. I am elated. Sitting on the toilet hurts the inner thigh of my injured leg, but it’s worth it. However, I am not to use the walker without someone standing by. The nurses don’t care for this. A pee pee call can be ignored for a while, but a call to help me get to the bathroom is another matter and they have to wait nearby until I’m finished to see me back to the bed.

In the afternoon, I spend another couple of hours in the chair, this time using the walker and Bill’s help to get from the bed to the chair. I’m still exhausted from the effort and from being upright, but it’s a relief to my sore back. What hurts the most is my tailbone, which has been bearing my weight for so long. I can now turn over on my right side for short amounts of time and Bill gives me a great back rub to try to get the circulation going.

Late in the day, I call my Napa orthopedics office, wanting to have an appointment to see a doctor within a day or two of getting home. I ask for the doctor who did my knee replacements. His assistant tells me he no longer does trauma cases. So, I have a new classification: trauma. She says they do have one doctor on staff who specializes in trauma. She mentions a name, but I don’t think to write it down. All this planning for the trip home and the time out of bed has exhausted me. I’m ready to sleep early.

Day Thirteen, May 5, Friday

Happy Cinco do Mayo! Nobody in Spain is celebrating! Hah! Plane reservations have been made for tomorrow on Iberian Airlines. Seville to Madrid is a bit less than an hour and a half. The non-stop from Madrid to San Francisco is thirteen hours. We have business class seats on both flights. At no cost, thank you Zurich.

We’ll be picked up by a driver at 6:15 a.m. That’s sure to be challenging, but when I call Maria, the patient relations gal, she says she’ll arrange it. In the afternoon, she brings me all my papers. We’ll meet the airport driver at the emergency entrance, as the main doors are locked at that hour. Bill will taxi over. Maria makes sure the night nurse knows she’ll need to get me dressed early in the a.m. Bill helps me reorganize my stuff and hangs the clothes I will wear—the same outfit I had on when the accident happened. Maybe some of the wrinkles will disappear overnight.

I ask Pepa if it is possible for me to take a shower. Despite the daily sponge baths, I don’t feel clean enough for an all-day excursion in public! She is most accommodating. She turns on the water and helps me to use the walker to get into the shower, where there is a chair. It is amazing to have warm water falling on my head, and dripping between my toes. Pepa hands me a clean towel and puts me in a fresh gown. Fantastic!

Dr. de la Cuesta has heard my concern about how I’m going to have meds when I get home. Bill will give me a Heparin injection on the plane and I’ll need to continue shots daily for a month. He comes by with prescriptions for the injections and pills I have been taking and tells Bill where to find a nearby pharmacy.

I call my long-time physical therapist’s office to give a heads up that I’m going to need their services. Rob is always scheduled weeks out. I leave a message with someone at 7 a.m. their time, but dear Rob calls me right back and we have a long chat. He tells me I should be able to receive initial PT at home and when I’m able to walk, he’ll be ready for me. I leave a message for my primary care physician, hoping he can do something about starting a referral for physical therapy.

I realize I haven’t succeeded in getting an appointment with an orthopedist. I call the Napa office again.

I say, “I called you a couple of days ago and talked to Dr. Diana’s assistant. I want to make an appointment with the trauma doctor, but I don’t remember his name.”

The receptionist answers, “We don’t have a trauma doctor. Do you want to leave a message for Dr. Diana?”

I know that won’t help and I’m not going to give up so easy. “Can you read the list of all the orthopedists on staff? I remember the name began with a hard “K” sound.”

She reads the list and there’s only one that fits. “Can you connect me to Dr. Caravelli’s assistant?”

It’s my lucky day. I leave a message for someone named Christina, and to my amazement, she calls me back in less than five minutes. And gives me an appointment for May 12. That’s a week after I’ll be home.

Day Fourteen, May 6, Saturday

All goes as planned. I’m awake before the alarm goes off. A nurse comes in and helps me dress and close up my bags. Bill comes to my room early, dragging his suitcase. They put me in a wheelchair and help us get down to the emergency entrance with all of our luggage. A driver is waiting with an SUV. It takes some effort to get me into the back seat with my leg straight. Not the most comfortable, but the ride to the airport is short. Bill and I wait while the driver goes in search of a wheelchair assistant. This kind man sticks around until we are checked in for the flight and in the capable hands of someone to push the chair.

The orders are for me to be in a wheelchair past the gate, all the way to my airplane seat. This requires a transfer to a narrower wheelchair before we enter the plane. We are of course boarded before anyone else. My assigned seat is the first aisle seat on the plane. Alas, it’s a bulkhead seat, with not enough room to sit with my leg straight in its brace. I would have been better off with two economy seats, but we’re not about to complain. I can only sit with my leg in the aisle, my foot up against the doorway that every passenger will come through. A flight attendant stands on the other side of the opening, pointing out my foot to everyone who boards, saying “Cuidate” or some Spanish version of “watch out for the foot.” The folks who aren’t totally out to lunch smile at me and step gingerly past.

During the flight a male flight attendant manages to bump my foot every time he walks through that door. Thank God it’s a short flight.

When the plane lands in Madrid, I expect to be exited the way we came in, but everyone with mobility issues—and there are a handful of us—are asked to wait until everyone else has departed. Then a side door of the plane opens up and voila, there is a room waiting for us to be rolled into. It’s a people mover of some sort. Once we are loaded in with our carry-on luggage and the wheelchairs secured by the operator, the whole room moves down, down, down to the tarmac, where it morphs into a kind of bus. We travel for maybe ten minutes to the international terminal.

The operator pushes me into the terminal, where we are placed in an open area, which must be labelled “handicapped.” We’re in a sea of wheelchairs. Staff with brightly colored vests, labelled on the back with a wheelchair symbol, are walking around, hands holding multiple boarding passes. They are directing wheelchair pushers to take different passengers to different gates. It’s busy and loud, but fascinating. I decide I want to visit the labelled handicapped ladies’ room that is right in front of me, so push my wheelchair that way, hoping they’re not calling our names before I’m done. It’s a big space with lots of rails to hold onto. Relieved to be relieved, I rejoin Bill. A pusher takes us to the area where the gates are and leaves us. We’re supposed to wait for someone to take us to our gate. After a bit, Bill reads the electronic gate information and sees our flight is beginning to board. He goes to a counter to ask what’s up. A nice gal comes to push me.

There are overhead electronic signs flashing how long a walk it is to each gate area. Ours says fifteen minutes. Is this enough time? There’s no point in worrying, but I do anyway. We move in the right direction and the next sign says ten minutes. I feel like we’re in a race. I tell Bill, “They’re not going to leave without us.” Although I have certainly had the experience in the US of arriving at the gate before departure but not being allowed to board! We arrive with plenty of time and get pushed to the plane’s entrance. Another transfer to a narrower rolling chair. Once again, my seat is the first one, one of those pods that I’ve never had the pleasure to use on a long flight. It would be great if I were able bodied, but I can’t seem to position my leg for comfort. Bill is unfortunately not directly next to me, but one seat back across the aisle.

This is a daytime flight, so I won’t need to sleep, but the hours go by interminably slowly. I take the brace off, put it back on, trying without success to get comfortable. Bill has an animated discussion with the woman sitting next to him. Fine. I explore all the little extras you get with business class. Socks and eye pillows and little treats. Nice but unnecessary. I try the seat in all of its different positions. I play with the WiFi, watch a movie. Just can’t get cozy.

When the time is right for my injection, I pull out the pre-loaded syringe and gaze in Bill’s direction. He’s sound asleep. So, I decide to give it a try, pull up my top, grab some stomach and push it in. No problem. It’s a very fine needle.

After a while the inevitable call to nature can’t be ignored any longer. There is a standard restroom very close to my seat, but that is not going to work with my leg in its brace. I signal the flight attendant. It seems the handicapped restroom is at the other end of the plane. She solicits the help of another attendant, who is pushing the tiniest rolling chair I have ever seen. The aisle is maybe eighteen inches wide and this seat leaves maybe an inch on each side. I transfer myself to the seat and the fellow positions himself to pull the chair. The female attendant on the other end holds my leg out straight. This is how we roll from the front to the back of the plane. The restroom is big, with lots of bars to hold onto and I’m hopping just fine. The two attendants push me back to my seat.

The second time I use the restroom is late in the flight, when lots of passengers are asleep. I disturb their arms and their blankets as I am rolled down the aisle. On my return, I tell Bill, “Everyone on this plane knows when I have to pee.”

We are met at SFO by yet another wheelchair attendant, who takes us to luggage claim. Once Bill has his bag, he goes off to get his car. The attendant stays with me until my bag comes off, then takes it and me out to the curb. It is afternoon in San Francisco, although I’m in bedtime mode. The attendant leaves me and the wheelchair on the curb with my luggage and I wait for Bill. He finally pulls over to the curb and helps me get in. He has arranged the back seat so that I can lean on something soft against the door and have my legs on the seat in front of me. I talk to him nonstop for the hour and a half it takes to drive to Napa, worried he may be sleepy.

We pull into my driveway and Bill finds the wheelchair on the porch and gets me into it. I am so happy to see Cousin Lyn, who has let herself in and is ready for the invalid. She opens the door to the garage, where it is easier to get me up the steps. Bill leaves us and Lyn helps me get out of my clothes and into a nightgown.

I fall into my bed. My own sweet, soft, comforting bed. I am so ready to sleep.

Epilogue

It’s been four months since my surgery. Had I known then how long this was going to take, I would have been very depressed. I look back one month, one week at a time at all the progress I have made.

At first, I was in a wheelchair and was exhausted every day by mid-afternoon, never going out except to see the doctor. Then I was able to use a walker, but needed a driver to go anywhere. Finally, I was able to drive myself to physical therapy. Now I get around with just a cane.

At first Lyn needed to help me use crutches to get into the shower. Then I learned to navigate from wheelchair to shower chair without assistance. Eventually I abandoned the wheelchair and found a way to get in with the walker. Now the shower chair is gone and the bath rug is back on the floor.

I went without daily mail, having to call and ask friends to bring it in from the box on the curb. Once I could get into the car, I would pull up close enough to grab my mail through the window. Then I used the walker, and now the cane to navigate both ways.

At first, using crutches to go down the three steps into the garage was terrifying, so much so that I tried to hop and sprained my good ankle back in May. That was a painful lesson, as I still had to put all my weight on that leg when I stood up. Then I learned to use one crutch and the handrail to get down the steps. I still needed a wheelchair or walker to get to the car, once I was in the garage. Now steps are not problem, although I still use the cane and take them one at a time.

I learned to have groceries delivered (although never exactly what I ordered). Or to order online and pick up at the designated spot. I can now manage a short trip to the grocery store or the farmers’ market, only limited by the weight and bulk I can carry. I can cook, do laundry, wash dishes, change sheets, and take the dog for a short walk, but not all on the same day. I plot my physical activity, spreading it out so as to not have pain in my leg or such exhaustion that I’m in bed at 8 p.m.

I suspect the effects of this injury will be with me for a long time. My physical therapist trusts me to judge how much exertion is the right amount. But I want to know when I’ll be able to walk my usual three miles. He doesn’t have an answer for that, but thinks I’m doing great, that when the accident happened, I was lucky to be in good physical health with well exercised muscles. I long to go on a hike, but wonder how afraid I will be about falling. I’ve been assured my healed femur will be stronger than ever and if (i.e., when) I do fall, I’ll be more likely to break something else.

So, yes, after four months, I realize my life has changed radically. I read about all the wonderful events happening in town or across the bay and know many of them are too much for me. I’ll heal faster if I spend most of my time at home, reading a book, watching TV, writing, and doing my exercises. But having just celebrated my 77th birthday, I also realize I’m lucky to be alive and am determined to make the most of my remaining years. I’ll continue what I have done since that fateful day in April: accept whatever life brings my way, work with the inevitable limitations, and live life to the fullest possible.

Oh my! This is like reading a nightmare–I’m so glad you are writing this down. If nothing else, it is a testament to how far you have come since the fall!

LikeLike

Hi, Lenore

I just finished reading your well-written piece about your travails. Although your injury was much more serious than the one I sustained in my own mishap when I was traveling in Peru a few years back and tripped on pothole in a sidewalk in Iquitos, deep in the jungle, I felt pangs of empathy with your ordeal. Mine was a broken shoulder and a trip to a public health hospital emergency department in a security guard’s jeep, with all the trauma that entailed (including a misdiagnosis). Through the assistance of a travel insurance nurse who paved the way, and a neighbor rounded up by my wife who is a native Spanish speaker here at home, I ended up in a private Adventist hospital – infinitely better that where I was but still very much third world with furnishings and equipment that looked like it was straight out of M.A.S.H. The difference between public and private health care in other countries is staggering. We can swap stories one of these days. In the meantime, thanks for the opportunity to read yours.

LikeLike

Thanks, Marty. I do want to hear more about your ordeal! In the jungle!

LikeLike

Lenore, greetings from a long ago classmate in Chelmsford MA (who now lives in Houston TX). Although our lives have not intertwined since elementary school, I did follow your journey with your broken leg. Your blog was very inciteful as to your determination. May you continue to heal internally and externally. Enjoy life again as you have done in the past. Maybe someday I will be in CA and get in touch with you.

Paula McKittrick Korber

LikeLike

Thanks, Paula. Do let me know if you get to Napa Valley! I have made an excellent recovery. Now walking with a cane and without it some of the time! I enjoyed seeing a few of the folks from elementary school a few years back when I was in Mass.

LikeLike

Goodness, what an ordeal. You write so well I could almost feel the discomforts you endured – kept reading to learn how you escaped.

LikeLike

Thanks, Paul. Glad it kept your interest.

LikeLike

Reading your description of what happened to you in Spain was like reading a good book . It was very hard to put down . What an ordeal you went through ! I’m very glad you are doing much better. All my best . Tim Brophy.

LikeLike